Jeremy.

INTRODUCTION:

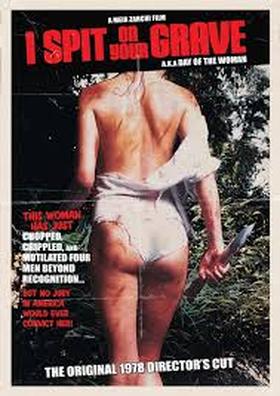

Ever since the creation of man and woman people have always drifted towards the idea of horror. It was a way to represent the evil and monsters that lies in every human soul. Early work by Edgar Allen Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson and Bram Stoker proved this to the world by releasing a slate of popular horror novels that related to these themes of death, evil, monsters and fears of society. When the creation of film became reality filmmakers from around the globe started to take these dark themes that were so prominent and evolved them to moving pictures. The results were astonishing and films like George Melies 1896 short film The Haunted Castle put the horror genre on the map. From this point forward more and more filmmakers started experimenting with the genre. This experimenting soon led to one of the hottest issues when it comes to the horror genre; the way feminism is represented. We first see this idea become prominent in the era of the Universal monster films where we saw women playing a single role which was to be the object that the monster desired. The fact that these women were so beautiful caused the monster to capture them making them damsels in distress. This caused the opportunity of the strong male character to come in and save the weak, helpless women from the clutches of the monster. As Carl Denham says in King Kong “It was not the airplane that killed the beast. It was beauty that killed the beast” (AFI 100 years, 100 movie quotes). As the horror genre moved past the over saturation of monster films and entered the 1960’s roles started to shift quite rapidly for women roles in the genre. 1960 was a very prominent year for females in the genre. Films like Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom presented the audience with its first glimpse of what would soon become known as The Final Girl. Characters like Lila Crane (Vera Miles) and Helen Stephens (Anna Massley) brought these ideas to life. The Final Girl theory is best described by horror theorist Carol J Clover in her famous book Men, Women and Chainsaws, Clover writes, “ The image of the distressed female most likely to linger in memory is the image of the one who did not die: the survivor, or Final Girl. She is the one who encounters the mutilated bodies of her friends and perceives the full extent of the preceding horror and of her own peril; who is chased, cornered, wounded; whom we see scream, stagger, fall, rise and scream again she is an abject terror personified” (35). While Lila Crane and Helen Stephens do follow the basic tropes of the Final Girl, we did not see the idea become prominent until 1978 with John Carpenter’s film Halloween. The fact that it took almost eighteen years for the Final Girl to be a staple of the horror genre is really represented by what was occurring around the country with the popularity of the second-wave feminist movement. The movement saw females protesting issues such as rape, domestic violence, abortion and access to childcare (Gordon). Feminist writers became prominent during the second-wave feminist movement and often saw horror as a degrading genre, especially rape-revenge films. The criteria for rape-revenge films are simple. First, a woman is raped by a single individual or group. The woman is then left for dead by these men. Second, the woman ends up surviving and spends a short period of time rejuvenating their mindset while at the same time realizing that they must take matters into their own hands. The final act shows the woman seeking revenge against her attacker(s) which often leads them to very gruesome and horrifying death(s). The moment that people read the criteria of rape-revenge films, they automatically think that the films are anti-feminist because they show men being in power and taking advantage of vulnerable women. That is not always the case though because individuals like myself actually think that these films are describing pro-feminist ideas. The fact that these women are taking matters into their own hands and proving themselves to society is showing that they are not just women who are here to be abused. The most debated film that falls under into category of rape-revenge falling under anti or pro feminist is Meir Zarchi’s film I Spit on Your Grave which Roger Ebert calls “A vile bag of garbage that is so sick, reprehensible and contemptible that I can hardly believe it’s playing in respectable theaters, such as Plitt’s United Artist.” In the film, we follow our leading character Jennifer, a writer from New York that decides to rent out a cottage in the country to focus on her new book. When Jennifer arrives we are introduced to our main male antagonists; Johnny (Eron Tabor), Stanley (Anthony Nichols), Andy (Gunter Kleemann) and a mentally challenged man Matthew (Richard Pace). One day after Jennifer is sun tanning in her canoe, she is surprised by Stanley and Andy, who takes her boat to the shore when they arrive Jennifer is beaten and raped by all four men in an uncomfortable set of sequences spanning almost 40 minutes of the 101-minute runtime. After being left to die Jennifer plans her retribution and seeks her revenge on the group through a series of disturbing and brutal murders. Two film theorists that people discuss most when thinking about the horror genre and rape revenge films is Laura Muvley’s 1975 article Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema and Barbra Creed’s 1986 article Horror and the Monstrous Feminine. While both would see I Spit on Your Grave through an anti-feminist lens, there are a lot of examples throughout the film that de-bunks both Mulvey’s theory as well as Creed’s.

MULVEY’S ARGUMENT:

Laura Mulvey’s 1975 article Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema is often quoted by many individuals as being one of the most important feminist film pieces to ever be written. The article was written in the midst of the second-wave feminist movement which saw more females writing academic pieces. It is hard to argue against that Mulvey’s piece was not the most influential to come out during the time. In the article, Mulvey uses a psychoanalytic motive to describe how cinema is seen as a “political weapon, which is used to demonstrate the way the unconscious of patriarchal society has structured film form” (711). Using this idea as the basis for the rest of her article Mulvey writes that the mindset of Hollywood narrative films is to use women to provide an enjoyable viewing experience for men. This use of women for enjoyment soon became known as the male gaze. The gaze objectified women even further with never allowing them a gaze of their own; it was strictly a male privilege. This gaze was always produced by either a masculine man hero or through the use of the camera. This idea of the gaze soon became a popular way to dissect horror films. It seemed like most of the films being released followed Mulvey’s ideas, but Meir Zarchi wanted to de-bunk these ideas in I Spit on Your Grave. Zarchi takes his time though to de-bunk Mulvey’s idea, which is a very interesting thing to note. He realizes the concept of the gaze and shoves it down the audience’s throat during the first act of the film. This is seen during the opening sequence of the film where we see Jennifer leaving to go on her trip. In the scene, we are placed at a voyeuristic distance as we watch Jennifer packing her car. We watch her, but it is not until she walks towards the driver’s door are we jolted forward as we are now able to examine Jennifer’s body in detail, Zarchi knows this is going to get the audience excited. It is only when Jennifer pulls away does she gaze into the camera for a short moment. It is not a long gaze, but it shows that she is recognizing right off the bat that Jennifer knows she is not allowed a gaze. The fact is that she acknowledges the audience and shows that she knows her main purpose is to be looked at. As the film continues we start to see Zarchi get “rid” of this gaze more frequently. For example, when Jennifer is unpacking her things at her cabin, she comes across a pistol at the bottom of a dresser drawer. The moment that she acknowledges the pistol she hears a knock at the door. She looks towards the direction of the camera (presumably where the door is) and back down at the pistol once more. The importance of Jennifer finding the pistol (which is usually associated with male power) is to acknowledge the male audience gaze and showing that she is soon going to “kill” off the audience gaze and replace it with her own. As the film continues we start to see the gaze shift from the masculine perspective to Jennifer’s more feminine one. This shift occurs after the rape sequences and continues throughout the last act of the film where Jennifer seeks her revenge. It is important to note that each murder that Jennifer partakes in against the group attacks the male gaze harsher each time. Let’s first look at the murder that occurs against Matthew. In the scene, Jennifer orders groceries from the store that Matthew works at. Because Matthew is mentally challenged he is required to do the basic necessities around the shop which includes delivering groceries. When Matthew arrives to Jennifer’s cabin, we see Jennifer taking full advantage of the male gaze by wearing a see-through shirt. This is obviously used to seduce Matthew as well as the audience. Jennifer continues to talk dirty to Matthew as they approach the lakeshore. Jennifer goes as far as taking Matthew’s virginity, something that he was searching to lose throughout the film. It is at the moment where Matthew is about to finish that Jennifer ties a noose around Matthew’s neck and hangs him like a slab of meat. So what comments is Zarchi making during this first murder? It is a rather simple one, instead of Jennifer running to a police officer or another man, we see her being able to handle the situation by showing the weakness in every heterosexual male; sexual activities. Jennifer disrespects Matthew and the male audience the same way that they treated her, like a useless piece of meat. The second murder that occurs happens against Johnny. In this scene, Jennifer performs the same seducing acts that worked against Mathew but this time Jennifer takes Johnny to the same spot where she was raped. When they arrive, Jennifer forces Johnny to get nude; when Johnny is undressing Jennifer pulls out the pistol that was seen earlier on in the film. Jennifer then stands in a shooting position as she places the gun towards Johnny and the camera. This is showing Johnny and the audience how much the perspective has shifted from a dominant masculine power to a dominant feminine power. Jennifer then walks up to Johnny and places the pistol in his mouth and slides it back and forth. Jennifer is obviously representing the oral sex she was forced to perform but also creates the fear in Johnny that he is going to now be looked at as a female. As Jennifer continues to taunt Johnny she gets another idea and decides to bring him back to her cabin. Once again even as these events are occurring Johnny is still thinking only with his penis and not his brain. When they arrive to Jennifer’s house, both get into the bathtub to take a bath. As Jennifer starts pleasuring Johnny with her hand, she grabs a large kitchen knife and slips it into the tub. As Jennifer continues to pleasure Johnny the one thing that every male fear occurs; Jennifer castrates Johnny. It is at this moment that Jennifer has finally taken full control of the masculinity in the characters as well as the audience. This is because she has taken the one thing that is associated with male power; the penis. As Stanley and Andy try to figure out what happened to their friends, we see Jennifer in the strongest state she has been in throughout the film. In the sequence, we see Stanley and Andy driving their boat to the cabin, as Andy goes off shore with an axe in hand, Stanley continues to drive around. Jennifer swims out to the post and pushes Stanley overboard before he realizes what has occurred. As Andy swims back to the boat to rescue his friend Jennifer kicks him in the genitals causing him to drop the axe. Jennifer then stands over Andy as the camera is placed in Andy’s perspective. The camera is tilted up looking up at Jennifer, who is now shown as a very intimidating and strong figure. Jennifer then raises the axe above her head and swings it towards Andy making contact with his body numerous times. The fact that Jennifer is taking such large and masculine swings at Andy is showing the male audience that her rape experience did not make her weaker but instead stronger. When Stanley realizes what happened to Andy, we see him return to the boat and in a feminine way beg Jennifer not to kill him. As Jennifer stares at him with tears running down his face she lets out a large manly laugh. She looks at Stanley and says, “Suck it bitch” and turns on the boat motor decapitating Stanley. By Jennifer saying, “Suck it bitch” she is making a final statement to the male audience that there was a change occurring throughout the country and that women should no longer be looked at as vulnerable and weak but instead as strong and powerful.

CREED’S ARGUMENT:

The next theorist whom Zarchi de-bunks with I Spit on Your Grave is Australian writer Barbra Creed who is most famous for her book The Monstrous- Feminine: Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis. In her book Creed looks at the idea that feminism itself is monstrous. She writes about this idea by saying, “all human societies have a conception of the monstrous feminine, of what it is about woman that is shocking, terrifying, and horrific”(1). Creed is extra careful though explaining the importance of gender. She does not simply look at monsters but instead tries to understand what these monsters represent. Creed says, “I have used the term ‘monstrous- feminine because the term ‘female monster’ implies a simple reversal of ‘male monster’. The reasons why the monstrous feminine horrifies the audience are quite different from the reasons why male monsters horrify the audience… The phase monstrous-feminine emphasizes the importance of gender in the construction of her monstrosity”(3). This quote is very important when looking at I Spit on Your Grave because while most male characters would see Jennifer as a “biological freak”(Creed 6) , most females would see the opposite and see the males as the freaks. Zarchi paid close attention to this idea and shows the male audience that feminism isn’t monstrous, that masculinity is. This idea of the males being the monsters appears during the sequence where Jennifer first makes contact with her group of attackers. This occurs when Jennifer pulls up to the gas station where the group of attacker's works. We see Stanley and Andy fighting over a large knife. The knife conveys a phallic symbol which shows that Stanley and Andy are monstrous and are fighting over this knife to regain their masculinity. When they see Jennifer, they both stop fighting over the knife and look straight ahead towards her with expressionless faces. The significance that neither of them recaptured control of the knife shows that Stanley and Andy have not regained their masculinity and will evolve as monsters as they attempt to regain their masculinity. This appears again later in the film when the group is having a conversation about women and feminism. The conversation goes “Johnny says, ‘the New York broads are all loaded, Matthew.’ ‘Yeah they fuck around a lot,’ Stanley adds, ‘I’m going to go to New York and fuck all the broads there.’ ‘Yeah I’m going to do the same in California,’ Andy chimes in, ‘Sunset Strip is just swamped with broads looking to get laid.’ Stanley agrees: ‘Chicks come from all over the country to places like that for one reason—and that’s to get laid” (Clover 121). While the idea of these men going to a large city with the thoughts in their mind to rape women is disturbing in itself, but there is another issue here that lies deeper in these character's psyches that make it even more monstrous. It is the fact that these women from these large cities are better off than these male characters make them extremely jealous. They have been raised in a society where men are known for being the main breadwinners for the family. The idea of women actually being more successful makes them feel less than a man, and because of that they have to make up for this failure in their psyche. The only way for them to regain their masculinity is to rape these women who are successful. The next day when the group puts their plan into action do we see masculinity in its highest form of monstrosity. It is usually during these rape sequences that people see Jennifer as the monster because of the way she is shown. Not only is she dirty, but she wanders through the woods like a zombie. Even though many see Jennifer as a monster during these rape sequences it is actually the group of attackers who are monsters. This is because they have built up all this sexual frustration that they do not care about anyone else but themselves. The camera plays a very interesting part in getting across masculinity as monsters during the scenes where the men beat and rape Jennifer one by one. The camera is placed in Jennifer’s perspective as it placed at a low angle and tilted up to see the hideous faces of her attackers as they rape her. Zarchi is using these close-ups to not show how horrible rape is and what the men are doing to Jennifer but instead to focus on the true horrific event; her attackers. It is in the following events where Jennifer seeks revenge on her attackers do we see the “death” to the masculinity of these men as well as the attackers. Jennifer chops, slashes and hangs every monstrous masculine feature that belong to these men showing the audience (and the dead characters) that feminism is not the issue, its masculinity.

CONCLUSION:

The popularity of the horror genre is something that is not going to go away anytime soon. While the genre's popularity has increased and decreased over time it achieves a level of emotion that other genre films cannot reach. While Zarchi will always be remembered as directing one of the most disturbing and brutal films to come out during the major horror graze of the late 70s and 80s, it did not negate the fact that Zarchi was trying to do a little more than to disgust his audiences. Instead, Zarchi paid attention to the changes that were occurring during the second-wave feminist movement that was sweeping the country. Not only did he comment on these changes through Mulvey’s idea of the male gaze, but he was also able to notice the negative changes that were occurring in the male culture as well. The fact that men were attracted to the cinema to cheer on these women getting murdered (Ebert) let Zarchi show how monstrous male culture was becoming. While I Spit on Your Grave will never win any awards based on its aesthetics, it was able to achieve something that so few horror films from the past and future could achieve; a message. This message is the main thing that Spit will be remembered for and because of that it will always stand as one of the most influential horror films to be released during the era.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed